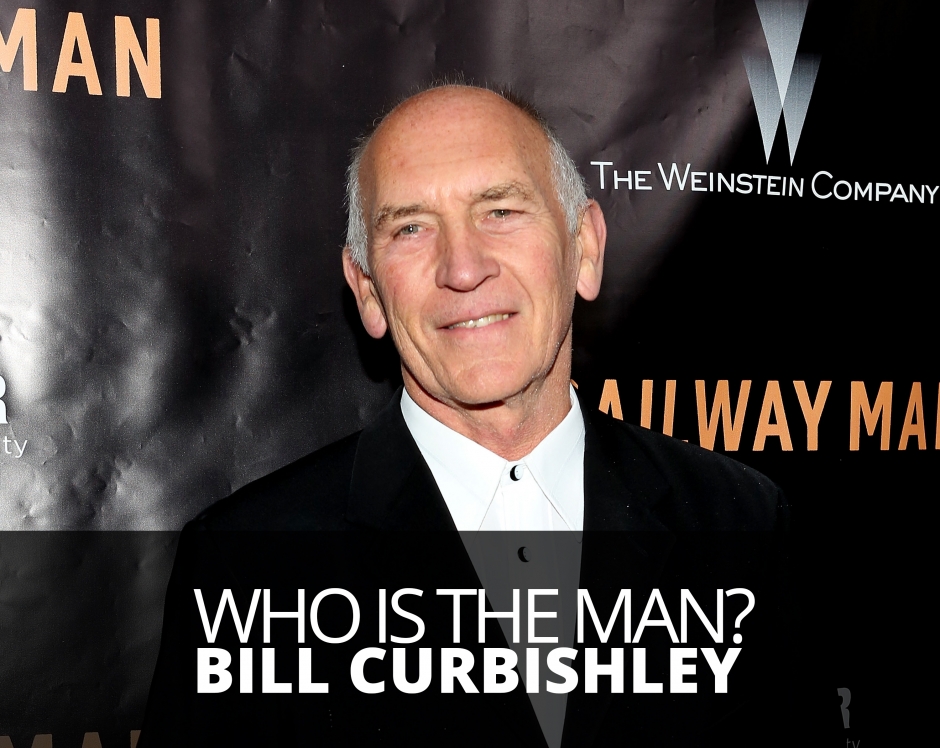

Bill Curbishley has led the most amazing life. Promoter and manager for The Who and Led Zeppelin, a film producer of such classics as Tommy and Quadrophenia and a man who mixes with the elite in society, his stories and experiences could fill a library, let alone a magazine article. With his background very similar to others and his personality modest and understated, Bernardo Moya finds out how he came to be The Man Behind The Who.

Back at school in the 1950s, Bill Curbishley’s teachers told him he wouldn’t amount to anything. Smiling at the memory at the memory he says, “If they’re still alive, I’d like to tell them I did!”

Born in Forest Gate in London’s East End, Bill was eldest of six children of a Royal Navy marine engineer. Living a relatively poor existence meant that “from a very early age, life was about work,” he recalls.

Tall for his age, Bill added fake years so he could work on building sites in the school holidays.

“To do four or six weeks work and earn a man’s wages was fantastic,” he affirms.

And that wasn’t the end of his work. Every evening at the local railway he sorted newspapers for newsagents. On Saturdays he forsook footie with his pals to push his laden Co-op wheelbarrow from Forest Gate up Wanstead Hill to sell firewood.

With school behind him, at his dad’s behest he worked as an apprentice draughtsman in an office in Westminster with a ticking clock that he counted to home time, he was so bored. Such a life clearly wasn’t for him – which is why he got work as a diver in Jersey before joining the merchant navy and travelled the world, jumping ship every time he came to a place he liked. “I honestly thought I may never come back again to these places.”

It’s a fascinating insight into the youthful mind of someone who went on to such great success. If anything can be said about Bill, it’s that he took his opportunities when they arose.

Finally back in London at the height of the Mod scene, Bill did what other Mods did – had fights with rockers at Brighton and listened to the amazing music of the time. In an environment surrounded by music he decided to “experiment” by joining a record production company run by a friend. It turned out to be quite an experiment. Luck soon struck when creative entrepreneur Peter Meaden, who’d previously discovered the Rolling Stones, offered Bill’s company a band called The High Numbers. He’d written their first two singles, ‘Zoot Suit’ and ‘I’m The Face’ specifically to attract the Mod audience and – as he closed the deal – he changed their name to The Who. The company also later signed Marc Bolan and T-Rex.

Those were heady times of hard work and hard play which saw Bill’s and the company’s star rising. But the luck didn’t run all one way. In those heady days of the 1960s two of his colleagues got into heroin, while his third business partner, Mike Shaw, was paralysed in a car crash. Under these pressures, the business began to collapse.

Nevertheless, The Who still wanted Bill to manage them and they soon called on him to negotiate movie rights to their ‘rock opera’ Tommy. Bill knew nothing about movies, but the situation was something that once again he was ready to rise to.

“I used to go away, pick people’s brains, go back the next day, negotiate a bit more, go away again, find out a bit more, pick their brains, go back.” One of the brains he picked was David Putnam’s, who went on to become Lord Putnam. Bill says proudly, “I managed to conclude a really good deal and Tommy got made.”

The movie was a massive hit, but Bill had difficulties to face with his other business partners who still had drug problems and whose court wrangling meant the management company’s assets were frozen.

For this reason Bill advised The Who to tour for the next two years to sustain themselves. Eventually they resolved their management difficulties and the 1973 album Quadrophenia became the subject for The Who’s next movie. Bill’s take on Quad was clear – the story was really about the music and, unlike Tommy, didn’t need big stars to carry it. He opted to use a completely unknown director and cast to tell the story of a young man’s disillusionment with his teenage ideals. Quadrophenia became a cult movie, despite American distributors wanting to dub the Cockney accents!

Luck also helped Bill’s success. When he invited American record company executives to listen to the band Golden Earring in London, a bomb scare evacuated the theatre. 2,500 people waited in the street for over an hour until police gave the all clear. “The next day I found the Americans at their hotel and I said ‘Why didn’t you come?’ They said, ‘We couldn’t get near the theatre. There were thousands of people in the street… We want to sign that band!'”

Life now seemed to go from success to success after the problems of the mid-1970s were put behind him. He even managed that other giant of rock music, Led Zeppelin. “I had Jimmy Page and Robert Plant. Jimmy Page was with me for like 14 years, Robert Plant was with me for 27 years,” he explains. “I had a short spell with UB40, too.” When asked how he did it, he says the main thing was to keep the bands’ jealousies in check, delegate day-to-day running of the band and jump in on the big decisions.

The music industry has changed a lot since those heady days, from the lack of variety to the complete lack of investment in anything new. “There’s nowhere near as much variety and selection as we used to have when we were younger, you know, it’s just not there,” he says. “Radio in America is sort of non-existent compared to what we had ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. It’s just not there.” And with music downloads becoming the norm, record companies are feeling it, so when it comes to advising potential music managers, Bill tells a cautionary tale. “[The music industry is] extremely difficult [right now], because what’s happening is that the distribution and selling of records has been monopolised by Apple. You’ve now got a generation that only buys single songs, single tracks. So the whole concept of an album as such, and the album being a musical journey, has sort of gone.” And to add insult to injury, according to Bill, Apple has hardly been forthcoming when it comes to investing money into young and upcoming artists, as the record labels of yesteryear used to. “They don’t invest one dime back into new artists, not a dime, they just sit there and take. So traditionally the record companies, even if you were on a bad deal and they were earning, not inordinate profits but big profits, they would always plough back into new artists, that was their business, to nurture and build new artists, they don’t do it anymore.”

The list of Bill’s other accomplishments over the years has been massive. The man who started stadium rock, the man who placed The Who at the 9/11 charity gig in such a way as to give them maximum exposure, recipient of the Kennedy Center Award, the USA’s highest arts award, the experiences of this man go on and on. But Bill says he has also learned to adjust to his success. It took him some time to realise he was working so hard from fear of being poor. As he puts it: “F.E.A.R. is False Evidence Appearing Real.” Having pulled back a little from his work with The Who he now spends more time with his family, knowing he has a reliable team to run the everyday business for him.

That said, Bill has many more projects in the pipeline, despite insisting he isn’t working as hard as previously. Maybe that’s true – but he certainly knows how to harness his energies effectively. That, perhaps, is the key to his success.

“You know, much of what we do in our lives can be wasted energy. One of the things that comes back to me quite often is a quote from Ghandi: ‘Why run so fast if you’re running in the wrong direction?’ It’s [about] choosing the right road.”

Bill Curbishley lists four practices central to his success:

1. A grasp both of English and maths means he understands the financial implications of negotiations down to the last penny.

2. Not drinking over a business lunch means he negotiates better.

3. Being honest means that people are willing to do a deal knowing they’ll get no surprises along the way.

4. Finally, he says he identifies the real kernel of problems to be focussed on.

Success At A Glance

- An attitude of willingness to work hard

- Being willing to “experiment” with what you’re doing

- Resilience when things go wrong

- Being creative and thinking innovatively

- Rising to a challenge and asking the help of others when you need it

- Delegating the day-to-day stuff to ensure you come in on the big decisions

- Flexibility in responding to problems

- Knowing how to turn luck to your advantage

- Identifying how to make the most of opportunities

- Work, work, work!

Bill Curbishley, The Who and The Teenage Cancer Trust

Bill Curbishley, manager of The Who, talks about his involvement with The Teenage Cancer Trust.

“Our doctor, Adrian Whiteson, started a trust called the Teenage Cancer Trust. There is a dire need for pre-surgical and post-surgical care for teenagers, because teenagers are in a special area of life – they’re not children, they’re not adults. What happens often is if they are unlucky enough to get a cancer they are put in with terminally ill old people or babies.

“This is not acceptable. Firstly teenagers don’t listen to anyone, other than other teenagers, as we know. And in that situation, they are full of fear. A little child doesn’t know the meaning or the connotations of death, but a teenager does.

” Adrian introduced us to his concept and what he wanted to do, and I’m really proud to say that after 17 years now we’ve got 22 units opened in the UK. Last year, we did a fundraiser in Los Angeles, and we had a unit opened in UCLA Hospital.

“We recently did a concert in New York in the theatre at Madison Square Garden, and we got Elvis Costello to open for us and support us, and he was fantastic, really good guy, and he came from Australia to do it, because he said this is something I really want to do. We raised $1.5 million, to open a unit in Sloan-Kettering in New York.

“I just feel, if I did nothing else, we’ve achieved fantastic things. I feel very privileged to be able to do that. And when I met five teenagers who’ve been affected by cancer talking about their futures now they’re clear of it, I felt that if they were the only five I ever met, it’s enough.”

Find out more about The Teenage Cancer Trust