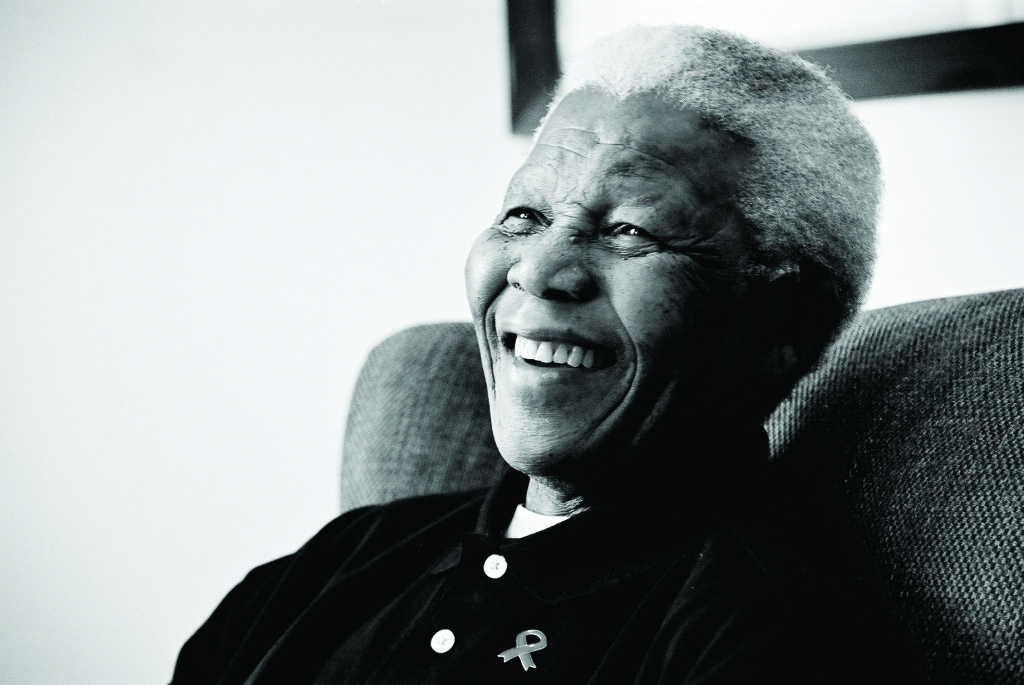

With mourning for Nelson Mandela’s death a global phenomenon, The Best You looks back at some of the turning points that made him not only the “father of the nation” of South Africa, but a universally recognised icon for perseverance, justice, dignity, wisdom – and freedom.

When Chief Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa named the child born into the Thembu Royal House in 1918 “Rolihlahla”, he had no idea how prophetic the name would be. Literally meaning in the Xhosa language “one who bends the tree”, it also means “troublemaker”.

Mandela’s father perhaps foreshadowed his son’s later defiance of authority when he defied a call from the local white magistrate to appear before him. In retaliation, the magistrate dismissed him from his post as chief. Losing much of his wealth, he was forced to relocate with his family to the little village of Qunu, where his wife’s family lived.

Here, young Mandela enjoyed a traditional upbringing, herding cattle from the age of five, playing on the veld, sleeping under the stars with other boys of the village, swapping tribal stories and learning to fight.

At the age of seven, Mandela’s natural talent and agile mind was spotted by a friend of the family, who suggested he attend the local Methodist school, and he became the first from his family to receive formal education. On arrival, he was given a new British Christian name by his teacher, Miss Mdingane. Why she chose it, no-one knows, but that was the moment Rolihlahla became Nelson Mandela.

Life at Qunu continued for two more years until Nelson’s father died. It was then that Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, acting regent of the Thembu people, repaid a debt of gratitude he owed Nelson’s father by adopting the boy.

Nelson now moved to Mqhekezweni, Jogintaba’s seat of power. Here, he began training as a royal adviser, attending tribal meetings and seeing for the first time indigenous African politics in action.

“I noticed how some speakers rambled… I grasped how others came to the matter at hand directly, and who made a set of arguments succinctly and cogently. I observed how some speakers used emotion and dramatic language, and tried to move the audience with such techniques, while others were sober and even, and shunned emotion.”

Jogintaba’s advice on leadership stayed with him, too: “A leader… is like a good shepherd. He stays behind his flock, letting the most nimble go on ahead, whereupon the others follow, not realizing they are being directed from behind.”

Further lessons came from the storytelling of an older chief, Chief Joyi, who told the people of the village of the history of the Thembu, of the coming of the white man and how it spelled disaster for the Africans. A similar message was delivered at the tribal coming-of-age ceremony where the boys of the village were circumcised. By no means a radical at that stage, he says: “At the time I looked on the white man not as an oppressor but as a benefactor, and I thought the chief was enormously ungrateful.”

But the chief’s words stayed with him, and over the following years he began to see the relationship between African and white man in a very different light.

Neverthless, at this time Mandela aspired to be a “black Englishman”. Going through the white-run education system at the Clarkebury Institute in the Transkei, Mandela adopted British customs, wearing boots for the very first time, eating (though at first awkwardly) with a knife and fork and becoming trained in the ways of modern European civilization. He admired the governor of the school, Reverend Harris, for his passionate belief in the good work he was doing in educating Africans, a view Mandela reiterated many years later. Harris was humble, kind, firm and above all, fair. This was the trait Mandela admired most in others.

After his move to Healdtown College in Fort Beaufort Mandela was taught that “the best ideas were English ideas, the best government was English government and the best men were Englishmen.” But he began to see how strong personalities among the Africans could stand their ground against whites. The self-important and overbearing principal of the college, Dr Arthur Wellington was on a number of occasions put in his place by one African teacher, Reverend Mokitimi. Nelson began to realise that perhaps the white man was not the all-wise benefactor he had believed, and that the African did not always need to be his lackey.

As World War II broke out in Europe, Mandela’s education continued. He was a fervent supporter of Great Britain – wanting the country to stay free of the oppressive and racist regime of Nazism, and not yet seeing the irony in such a view.

He also started to express his own sense of justice. By 1940, he was studying law at Fort Hare University, the only black university in South Africa. In 1941, he refused to accept election to the student council as a protest against conditions at the establishment. He was eventually forced to leave the university because of his stance.

Many events opened Mandela’s mind to the injustices of white rule. But it was when he returned to Mqhekezweni and confronted an injustice from his own tribe – the threat of being forced into an arranged marriage that none of the parties wanted – that he and his adoptive brother, Justice, ran away to Johannesburg.

It was here that Mandela saw the way white capitalists ruthlessly exploited black labour in the gold mines to make the few whites at the top extraordinarily wealthy. It shocked Mandela, and his world view began to radically change. Impoverished and struggling to get work, he met the self-educated lawyer, Walter Sisulu, who secured him a job as a clerk in the liberal-minded law firm Witkin, Sidelsky and Eidelmann. Here he was introduced to Communism by a colleague, Nat Bregman, though he thought Communism misunderstood the problems in South Africa – emphasising as it did class rather than race as the criterion for oppression.

Even at this supposedly liberal establishment Mandela was exposed to further indignities. “I was dictating some information to a white secretary when a white client whom she knew came into the office. She was embarrassed, and to demonstrate that she was not taking dictation from an African, she took a sixpence from her purse and said stiffly, ‘Nelson, please go out and get me some shampoo from the chemist.’ I left and got her shampoo.”

In 1944 Mandela became a member of the African National Congress, which initially sought peaceful means of resistance to white oppression, modelling itself on the peaceful protests of Gandhi in India. By 1948 he had become chief executive of the Youth Wing of the ANC, and was being continually harassed and arrested by the white regime for his work.

These arrests were just another expression of the systemic racism of South African society, which was developing a more sinister instrument of oppression: the law. Throughout the preceding century and a half, African tribes had been dispossessed of their lands by whites through the steady processes of warfare and forced purchase. In each case, the whites had taken the best for themselves. By the late 1940s, the racist government was developing a whole new strategy.

The injustice incensed Mandela. After many attempts to fight the system legally, being banned from travelling and arrested on numerous occasions, in 1961 Mandela finally became convinced of the need for armed struggle against South Africa’s white oppressors.

He now co-founded and organised the MK Group, the military wing of the ANC, received training from Marxist revolutionaries and began to organise bomb attacks in South Africa.

Of his subsequent arrest along with nine others in 1963, the calls for the death penalty, and he and his fellow prisoners’ long years of imprisonment, much has been written.

Forced to dig out lime from a quarry in his early years of imprisonment on Robben Island, Mandela was refused sunglasses in the glaring light. His eyesight was permanently damaged, but his resolve held. While breaking rocks to make gravel, he successfully fought the South African Law Society who tried to have him struck off as a lawyer, writing legal letters from his jail cell at night. He found new ways to resist, working alongside his co-prisoners to outwit his guards. His resolve never broke. He maintained an unshakeable belief in justice, never wavering from his sense of the rightness of his cause.

During his incarceration, out of sight for 27 years, he never compromised. He refused to renounce the principles that had put him there – even when doing so would have meant release from prison.

Mandela, affectionately called Madiba after his Xhosa clan name by those who feel close to him, was an extraordinary man. As a symbol of the fight for right against the injustices of the South African Apartheid regime, Mandela became a world-recognised icon. But he also became far more than that.

After his release in 1990 and the election in which he became South Africa’s first president with a full mandate from blacks and whites, Mandela strove to heal the country’s deep divisions. He knew that for South Africa to survive in peace, blacks and whites needed to find a way to live together. His work and his legacy is a bigger story than that of one man’s fight for freedom for one particular group. It is one of striving for fairness and justice for all, whatever the colour and whatever the creed.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, did not simply “bend the tree” as his name foretold. He shook it, from roots to branches. He managed to bend the whole of South Africa to his vision of equality and justice.

Now that is a “troublemaker” of the very best kind.

Nelson Mandela At A Glance

- Born in 1918 in Qunu, Transkei region of South Africa

- Given the name Rolihlahla, meaning “troublemaker”

- In 1925 became first member of his family to go to school, aged 7

- Attended school and university at Fort Hare, where he met Oliver Tambo, who became a long time friend and freedom fighter

- Left Fort Hare without a law qualification after making a stand against the administration about the quality of food

- Ran away to Johannesburg to escape a forced marriage and met Walter Sisulu

- Joined the ANC in 1944 and became leader of the Youth Wing in 1948

- Strove for peaceful resistance to white domination, but increasingly began to realise that white rule might need to be stopped using force

- In 1961 co-founded the MK Group, the military wing of the ANC alongside Joe Slovo

- Commenced a campaign of sabotage through bombing, with the intention of affecting property and not taking life

- Tried and found guilty in 1964 of attempting to overthrow the government

- Sentence to life imprisonment rather than execution

- Became a symbol for South African injustice and a central figure in its eventual dismantling

- After his release in 1990, led negotiations with the South African government

- Elected as President of South Africa in 1994, the country’s first black chief executive

- Oversaw the setting up of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee, to bring peace between blacks and whites

- In 1999 he retired from politics, but continued his activism and philanthropy

- In 2007, he founded the group known as the Elders, a group of world leaders intent on solving world problems

- Died December 2013, aged 95

- Will be remembered as “the father of the South African nation” and for extraordinary resolve and his capacity to forgive