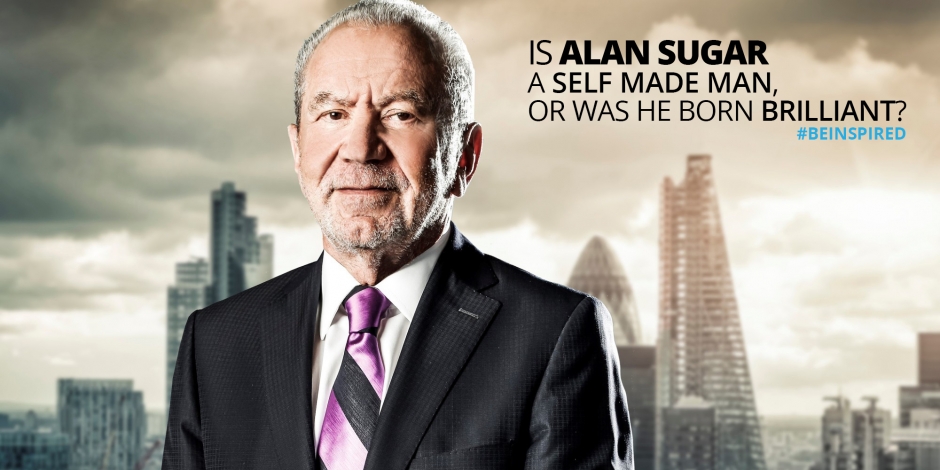

Alan Sugar is convinced that entrepreneurs are born and not made. But is he right? The Best You finds out.

“Entrepreneurial spirit is something you are born with, just like a concert pianist’s talent. Stick me in a room with a piano teacher for a year and maybe I’ll end up being able to give you a rendition of ‘Roll Out The Barrel’, but would I ever be a concert pianist playing at The Royal Albert Hall? Not in a million years. In the same way, you’ve either got entrepreneurial spirit, or you haven’t,” Lord Sugar says, unequivocally.

Renowned for his irascibility, he even has trouble with the word entrepreneur. “At the numerous talks I give around the country these days… there’ll be a Q and A session and it never fails to annoy me when somebody stands up and says ‘Hello, I’m an entrepreneur…’ I refer to my entrepreneurial spirit as I have been branded an entrepreneur so many times by so many people that I feel I’ve earned the right,” he say. Many, he believes, have not.

Lord Sugar’s success comes from an extraordinary combination of inspiration about what the market wants, flexibility to the customer’s needs, inventiveness (it was Sugar who came up with the idea of that great 1980s icon, the tower stereo system, and he was an early entrant into the home PC market), gut instinct, insight into people and an ability to learn from mistakes.

Nothing of this is suggested by his early life in a Clapton council flat during the late 1940s and ‘50s. His father, a clothes factory tailor, would occasionally alter clothes to earn a few extra pennies. Life was hard: “My parents did their best, but not being able to have what I wanted made me determined to do something for myself – to be self-sufficient.”

With rose-tinted joy he recalls his early days at his first school, Northwold Primary. It was an innocent time that was to change when he went to Brook House Comprehensive and encountered racism for the first time.

In his teens he went into his shell, virtually living the life of a recluse, lacking in confidence with others. It’s not true that he hid away at home, however. The young Alan had already found a passion for making money.

He tells a series of stories which highlight how he thought. One tells us that he had a sense of practicality, confidence and unabashedness.

At age 11, the story goes, he decided to make his mother a cake and asked his neighbours for the ingredients. When his mum came home and he showed her the cake, she immediately felt embarrassed at his asking neighbours for the ingredients. She only relaxed after their assurances that they were amused by him.

His sense of enterprise came early, too. Seeing someone throwing away sacks of material, he asked if he could have them. He took them to a rag and bone man who told him it was rubbish and paid him half a crown (12 and a half pence in modern money). When he discovered he had been “legged over” by the rag and bone man another side of the 11-year-old’s personality came. He went back, confronted him and demanded the proper price. “The rag and bone man slung two more shillings at me and told me to clear off,” he says.

Such a story reveals something else: he had a strong sense of right and wrong and was willing to fight his corner even then.

Sugar gives numerous accounts of identifying opportunities. Seeing builders resurfacing the roads, digging up and disposing of the tar-soaked wooden blocks the road was laid on, he organised a group of friends to chop them up so he could sell them as firelighters.

It was a short-lived operation. When older boys in the flats found out what he was doing, they took over and pushed him out. Again, he learned the lesson – always be aware that the competition is close behind.

All the while, Alan’s dad would shake his head at his money-making schemes. “It was a strange attitude,” he confides. “Many times I’d have to play down the success of my business activities because my father could not believe that someone so young could make so much money.” His dad’s caution highlights something else in Sugar. Self belief.

His was an extraordinary set of skills that he built upon when young. Whether he was making and selling ginger beer, becoming a photographer at bar mitzvahs, or printing and selling his own school magazine, Sugar just seemed to see ways to do things that would make money. Then got on and did them.

After leaving school and doing a short stint of statistical work with the Government, he moved into retail. He had several jobs, including retailing clothing on Saturdays and selling repaired televisions in the evenings. It gave him the opportunity to watch great salesmen at work and he picked up a new sets of skills that would be useful to him later. He makes no distinction between effective salespeople. As he says of the seller in Chelmsford market:

“Let me tell you, he is no different from the suited and booted executive with a fancy Powerpoint presentation, trying to sell Rolls-Royce engines to Boeing. The commodity may be different, the environment may be different, but the presentation and selling skills are exactly the same, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.”

Having seen other people do it, at 19 years old, he decided go it alone. He bought a van and £40 worth of aerials from a trader called Ronnie Marks. Four days later he’d made £60 profit, which was a lot of money at the time. This was the start of Amstrad, the Alan Michael Sugar Trading Company. He went from strength to strength selling electrical goods bought wholesale.

Sugar soon realised there was a better margin to be had from manufacturing items. He could undersell the competition and still make more profit for himself.

His first foray into manufacture was his plinth and cover for stereo record decks. “A lump of plastic and wood,” he says that he got cabinet makers in the East End to knock together cheaply.

He cut costs further when he had the plastic cover made by injection moulding rather than vacuum forming. His cost reduction philosophy was something he would continually apply to make items affordable for everyone. His next step was a logical one – to produce a cheap separate amplifier. With the Amstrad 8000 he started making electrical goods. “There I was, 24 years old, running my own factory, employing about 30 people,” he remembers. It was quite a story, and it had only just begun.

He faced problems along the way, but Alan Sugar found ways around them. To get over the three day week that restricted the power supply to his factory due to strikes, he ran a generator in the premises. When two of his workers stopped working and began intimidating his plant manager, he dragged them out of the pub and they turned nasty. Armed with a crowbar, his response was: “If either of you come near me, I’ll wrap it round your head.”

By the end of the 1970s, Sugar had factories in the UK, a large turnover and a healthy profit margin in the millions. He was experienced in the electronics sector and was ideally placed to take advantage of the massive 1980s electronics consumer boom that was to come as a result of cheaper, mass-produced components.

His philosophy was simple, he says: “Pile ’em high and sell ’em cheap.” His achievements were many. He undercut the professional business machine market. Word processors were selling at £5000-plus in the mid 1980s. To the astonishment of the Press he produced one for £399. It was the same with personal computers and tower stereo systems – the last being a concept he invented.

It was said of Alan Sugar back then that he knew every part of his business. He would sit on the assembly line when a product was first being produced and assemble it himself to understand its costings. He was also known for talking directly with employees on the factory floor.

Part of his success came from finding and building relationships with suppliers who could build his products cheaply and quickly. He found manufacturers in Japan who could deliver on time, to specification at the right price. In this way, throughout most of the 1980s, he outstripped the competition.

He was also unconventional. When Rupert Murdoch approached him to supply Sky Broadcasting with satellite receivers, he decided on his price point and then went hell-for-leather to reach it. It was the reverse of the normal way of doing things.

By the early 1990s, the huge consumer boom Amstrad had ridden was coming to an end. At its height, Amstrad had been worth £1.2 billion, but by 1992 was reporting losses of £72 million. Sugar saved the company from liquidation by a fire sale of his failed PC line and soldiered on. He also became chairman of Tottenham Hotspurs, a decision he was later to describe as “a waste of nine years of my life”. He set up Amsair, which provides executive flights and also bought IT company Viglen.

By 2007 Amstrad was essentially a maker of satellite dishes for BSkyB, and it was then that Sugar sold the company to Sky for £125 million. A year later he stepped down as Chairman.

He continues to be an entrepreneur with a brilliant understanding of people, and a direct understanding of the public’s needs. His renowned bluntness makes for great viewing on the BBC tv show The Apprentice. He reflects that he was never taught how to small talk when he was a child, and he finds parties and meetings in which people sit around not talking about why they’re there as a “waste of time”. To him, it is down to business straight away.

This has sometimes backfires on him. When in negotiations with one of his Japanese suppliers, a Mr Otake, he was once shown Otake’s latest electrical product, only to ask immediately how much it cost. Mr Otake, clearly proud of what he had produced, took exception and sulked. But at the same time, his interest in getting down to business means that – as he says himself – “what you see is what you get”.

Alan Sugar’s drive to succeed and his obsession for innovation haven’t waned as the years have gone by. His attitude of sturdy self-reliance, instinctively grasping what will work and what won’t, his ability to see to the core of problems quickly, his self-belief, humour and willingness to learn have all stood him in good stead.

He looks for these traits in The Apprentice, testing contestants for their entrepreneurial aptitude. He believes in putting them through the whole process of buying and selling at a basic level – of coming up with a brand, a slogan and a well-conceived product. At times putting his apprentices under massive pressure, he believes that the School of Hard Knocks provides a valuable education. He is the proof of it.

In 2009, Alan Sugar was elevated to the peerage. Lord Sugar of Clapton continues to be a major player in business with a personal net worth currently estimated at £770 million ($1.14 billion).

It’s tempting to say that, going from those early days of selling discarded wool to the present is a “rags to riches” story, but his life is far more than the cliché.

It is also more than the simple belief Lord Sugar holds that the entrepreneur is born, not made. Yes, his story is one of a man with unique innate talents, but it is also of someone willing to learn, adapt and listen to his instincts along the way.

Alan Sugar at a Glance

- Born 1947 to a poor Jewish family the youngest of four kids and grew up in a flat in Woolmer House council estate.

- He was not great at spelling at school and discovered a joy for maths only when he could see a use for it.

- From very young could see ways to make extra money, much to his dad’s embarrassment and unease.

- Dropped A levels in favour of work. Failed to find employment with IBM and worked briefly for a Government statistical office.

- As a teenager worked in retail before setting himself up selling his own goods. His first purchase was a batch of car aerials for which he paid £40.

- Formed Amstrad in 1968

- Invented the tower hi-fi system, introduced the Amstrad computer and the first cheap word processor.

- Stayed at the forefront of cheap technological innovation throughout the 1980s taking the company to a value of £1.2 billion.

- After disasters in the early 1990s, saved Amstrad from liquidation and continued to trade.

- Supplied the satellite dishes for BSkyB through Amstrad.

- Purchased other companies, including Betacom and Viglen and set up Amsair executive airline.

- Became Lord Sugar of Clapton in 2009.

- Continues to espouse his code of self-reliance and unique business style through hit TV series The Apprentice.

- Estimated worth: £770 million.