Pool of Gold

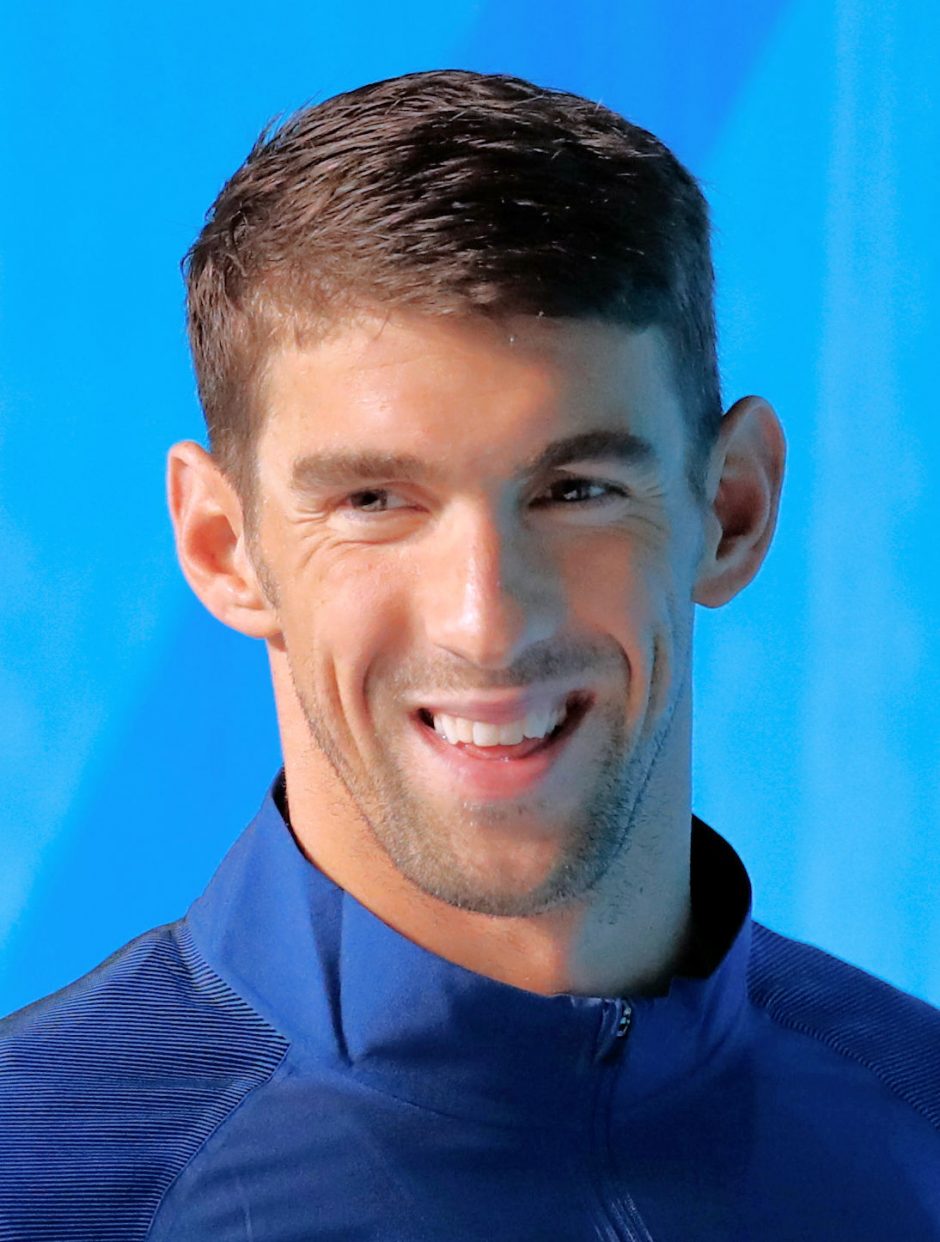

With 28 Olympic medals to his name, Michael Phelps is the most decorated Olympian ever and has won more Golds at a single Olympics than any other athlete. He has broken world records repeatedly in many different styles and distances, and has been described as the world’s most successful athlete of all time. Having announced his retirement after the Rio Olympics, The Best You looks at the phenomenon that is Phelps.

“I started swimming when I was seven,” Michael Phelps remembers. “Mom put me in a stroke clinic taught by one of her good friends, Cathy Lears. ‘I’m cold’, I remember saying… ‘I have to go to the bathroom… Can’t I just sit here and watch the other kids? I’ll stay here by the side’.”

Most of all, Phelps remembers he didn’t like putting his face under water; but when it came to the programme Cathy had for him, she was firm: “You’re going to learn,” she would tell him, “one way or the other.”

This led to more complaints and more whining, though Phelps concedes – “I finished every item on her plan.”

It wasn’t the most auspicious start to a swimming career.

In fact, though no-one knew it at the time, Phelps had ADHD – which meant he had boundless energy and terrible concentration.

“All everyone knew, in particular my mom, my sisters, and my coaches, was that I had all this energy and that I could bleed off a lot of it by playing sports: baseball, soccer, lacrosse, swimming, you name it,” he says.

Swimming turned the negative of ADHD into a positive.

“What I discovered soon after starting to swim was that the pool was a safe haven. I certainly couldn’t have put that into words then but can look back and see it now. Two walls at either end. Lane lines on either side. A black stripe on the bottom for direction. I could go fast in the pool, it turned out, in part because being in the pool slowed down my mind.”

So, after that early reluctance to put his face in the water, how did Michael Phelps come to dominate his sport so spectacularly?

Some of this comes from his personal traits: determination, stubbornness, imagination, attitude and having a bigger picture. But it also comes from outside: discipline, strong support and absolutely brilliant coaching.

Debbie, his mother, introduced him to swimming when he was a baby, taking him to the pool while his two older sisters swam. An educator who was used to working to bring out the best in children, Debbie recognised a passion in her children for swimming and did everything she could to help them. But there was no spoiling. Her disciplined approach applied at home, too. Homework, chores, tidiness were all given importance. Phelps asserts: “That work ethic, and that sense of teamwork, was always in our home. All of that went to the pool with me, from a very early age.”

His dad, Fred, was a good athlete – a college football player, and from him he got his athletic and competitive genes. “My father’s direction was simple: Go hard and, remember, good guys finish second. That didn’t mean that you were supposed to be a jerk, but it did mean that you were there to compete as hard as you could.”

Later in life, Phelps recognised that he had the perfect physique for swimming. He was tall at 6’4”,, and had an even wider “wingspan” at 6’7”. His body is long in comparison to his legs, allowing him to plane on the water, and his hand’s and feet are big, allowing him to get purchase through the water.

But natural ability wasn’t the whole story, as Phelps is quick to point out:

“In some sports, you can excel if you have natural talent. Not in swimming. You can have all the talent in the world, be built just the right way, but you can’t be good or get good without hard work. In swimming, there’s a direct connection between what you put into it and what you get out of it.”

Having seen the potential in him, Debbie sacrificed much of her time in supporting her son. It required “enormous dedication” he says. “It was a total reflection of who she is. And that’s something I am forever grateful for.”

So, what did she expect in return? “We had to have goals, drive, and determination. We would work for whatever we were going to get. We were going to strive for excellence, and to reach excellence you have to work at it and for it.”

Debbie introduced Phelps at the age of 11 to a coach who could bring him on. Bob Bowman remained his coach all the way through his swimming career. A highly intelligent man from a background of psychology and with interests ranging from sports to literature, science and classical music, he was far more than a coach. He became a close friend and guide to Phelps. In many ways, he became a strong father figure, especially because Phelps’s father and mother separated when he was seven.

The relationship between Phelps and Bowman is unique. At times it could be stormy, with Bowman seeming to need to break the wild unruly horse that was the young Phelps. They would chew each other out – and one time when Phelps wouldn’t do what he was asked as a teenager, Bowman called in both parents to back him up. There was nowhere for Phelps to hide, and he finally did as he was told.

Bowman introduced him to training techniques that are well-known among the elite sport world. What is surprising is just how effective they are in Phelps’s case. Take, for example, the practice of visualisation, which is a technique Phelps swears by. Phelps often uses visualisation during the nap periods he takes in the day in between training sessions.

“Before I doze off or immediately after I get up, I can visualise how I want the perfect race to go. I can see the start, the strokes, the walls, the turns, the finish, the strategy, all of it. It’s so vivid that I can see incredible detail, down even to the wake behind me. It’s my imagination at work, and I have a big imagination. Visualising like this is like programming a race in my head, and that programming sometimes seems to make it happen just as I had imagined it.”

Phelps also uses ‘visualisation’ to overcome problems:

“I can also see the worst race, the worst circumstances. That’s what I do to prepare myself for what might happen. It’s a good thing to visualise the bad stuff. It prepares you. Maybe you dive in and your goggles fill with water. What do you do? How do you respond? What is important right now? You have to have a plan.”

This ‘programming’ Phelps does can have startling effects. He believes strongly that if you can imagine it, you can make it happen. Where his mind goes, his body follows. This is more true when combined with another technique introduced to him by Bob Bowman: setting goals in writing. The results were startling, with Phelps finishing in exactly the times Bowman set him, down to the hundredth of a second. And these were all time he had never swum before!

There is also a deeply private and practical part to Phelps’s attitude. He won’t badmouth his competitors, and believes in keeping his own counsel.

“People who talk about what they’re going to do, nine times out of ten don’t back it up. It’s always better, and a whole lot smarter, not to say anything, to simply let the swimming do the talking. There’s a saying that goes precisely to the point, of course: Actions speak louder than words. That saying is 100 percent true.”

These are just a few of the mental techniques and attitudes Phelps uses, but there is also the physical side of things. No surprise to say that Phelps trains almost religiously, and sums it up in a simple phrase: make a habit of doing things others aren’t willing to do. He explains:

“Are you willing to go farther, work harder, be more committed and dedicated than anyone else? If others were inclined to take Sunday off, well, that just meant we might be one-seventh better.”

He goes on:

“For five years, from 1998 to 2003, we did not believe in days off. I had one because of a snowstorm, two more due to the removal of wisdom teeth. Christmas? See you at the pool. Thanksgiving? Pool. Birthdays? Pool. Sponsor obligations? Work them out around practice time.”

Meanwhile, the training was gruelling, with Bowman getting Phelps to concentrate on both speed and endurance. At times Phelps recalls climbing from the pool hardly able to stand, only to climb on the platform and dive back in to swim more lengths. At times, he averaged 85,000 metres per week in the pool. He certainly did not think that to have the confidence to take on the world, it was enough to visualise. As Phelps puts it:

“You can’t dream up confidence. Confidence is born of demonstrated ability.”

So, how does Phelps sum up his own achievement, now that he was retired? His answer:

“With hard work, with belief, with confidence and trust in yourself and those around you, there are no limits. Perseverance, determination, commitment, and courage―those things are real. The desire for redemption drives you. And the will to succeed―it’s everything.”

He pauses.

“Dreams really can come true.”

Doctor and Mind Coach Stephen Simpson explains Michael Phelps rise to the very top

“I work with elite performers, and it doesn’t matter whether they’re a top banker, golfer, or poker player – the methods I use are the same, albeit with some creative adaptation for each individual. This is good news for me – and more importantly it is good news for you too – because it means you can use these secrets to achieve more in your life, too.

I use seven secrets. There are many more, but seven is about the most that any person can remember. These are more than enough for anybody. As you’ve read, Phelps uses them all and it’s a tough call to suggest which is the most important one.

My suggestion is that it is the power of Phelps’s visualisation skills. He has taken them to the nth degree. It’s one thing to play comforting movies in your mind of you swimming the perfect race, then receiving the gold medal and biting it. It’s quite another thing to construct a different movie painting a lurid picture in agonising detail of all of the possible things that can go wrong.

However this exercise is at least as important as building a compelling visualisation of success. All champions do this because they know the danger of surprises. Concentration is broken, the power of the moment has been destroyed, and in these circumstances competitors often freeze.

Last year I wrote an article in this magazine about Formula One world champion racing driver Lewis Hamilton is just like Phelps. Hamilton spends hours in a simulator practising all the things that can go wrong in his race, and so is prepared for the unexpected, with nothing that has not been imagined.

Phelps reinforces his visualisation by adding another step to his process. He writes notes to himself, putting his goals on paper. This is a powerful way to hardwire a virtual thought so that it becomes an unconscious reality. It is an illuminating example demonstrating that ‘thoughts become things’, as highlighted in the book The Secret.

So write a note to yourself now, date it in the future, and describe the celebrations associated with your success. Add in as many details of what you can see, feel, and hear in your mind. Do not forget your emotions either, because these are powerful anchors, and will prime your next project for ignition and success too.”