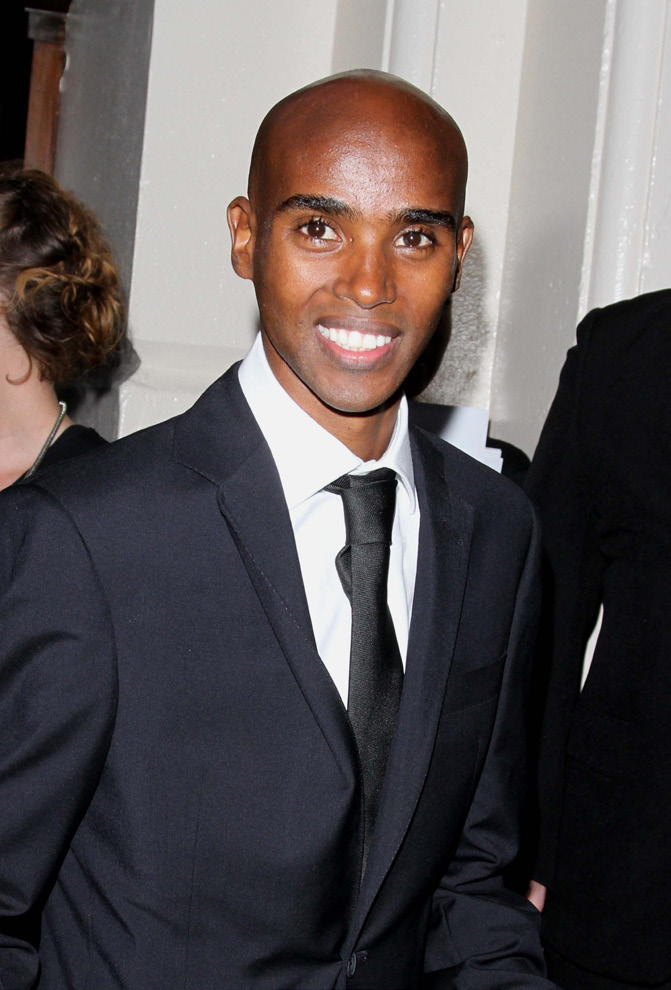

He’s one of Britain’s greatest-ever athletes — but Mo Farah’s career almost didn’t happen. Fresh from gold medal success at the Rio Olympics, The Best You looks back at a career built on sacrifice and hard work. Mo Farah’s story shows how it isn’t enough to have great talent, a dedicated team, and teachers and coaches rooting for you. There has to be something else, that comes both from the inside and out.

Born in humble beginnings in Somalia, the younger of twins, Mo moved to the United Kingdom in 1992 when he was nine years old, to join his dad who had already moved to London for work. Due to unfortunate circumstances, he left his twin brother, Hassan, behind in Somalia, and didn’t see him again for 12 years. During this time he moved in with his Aunt Kinsi, attending Feltham Community College, West London.

At school, Mo struggled to learn English, partially because he is dyslexic but also because he was so full of energy he found it hard to sit still. He continually got into trouble for misbehaving, though he was well liked by his classmates, and would make animal noises at the back of the room for their entertainment. He recalls that he was perpetually being sent to see the headmaster.

It would have been easy for him to fall in with a bad crowd, with so much energy and with no point of focus, but an outlet came for Mo in the form of sport. Though he was an avid football player, his Physical Eduction teacher, Alan Watkins, saw that he had a natural ability to run distance, and persuaded him to take part in athletics at the Borough of Hounslow Athletics Club. Mo was far more interested in playing football – it was his deep-seated passion, and it was only when Alan did a deal with him, allowing him to play football for an hour before heading to the track, that he finally relented and went along regularly.

The Hounslow track was far from ideal. It was run down, with the spectator stands long gone, and with only a portakabin as a shelter for the athletes. Mo continued to be lukewarm about his running ability, relying on his natural talent to see him through races. But at the same time he began to find satisfaction in his obvious aptitude for running.

Mo’s progress to becoming a serious, world-beating athlete was not entirely conventional. Though he had been talent spotted, he continued to be easily distracted from races. Perhaps this is understandable – Somali culture doesn’t understand the value of running as a sport, and members of his family never attended his races as a child. Alan, however, took him under his wing and at times Mo showed real passion for racing. He speaks of the athletics community as friendly and one big family – and perhaps that emotional drive also pushed him on. Mo was soon winning races, and as he began to see more results in the circuit, and build up a reputation, he became increasingly committed to the sport.

A turning point came when Mo was selected to attend the British Olympics futures camp in Florida when he was 14. He met sporting greats and saw the amazing facilities a top athlete could expect to use. It resonated with Mo, and on his return he was sure he wanted to be runner.

Mo began to train harder and soon after he won the English schools cross country championship – his first major national title – and in 2001 aged just 15 he won the 5000m junior championship title – his first international title.

After college, Mo was tempted to join the army but was talked out of to by Alan Storey, a coach and Head of Endurance for UK Athletics. Instead, Alan persuaded Mo to attend the recently formed Endurance and Performance coaching centre at St Mary’s University, Twickenham.

Mo had all the support he needed, and this moment could have been the start of a powerful surge for him, but his commitment wasn’t yet sealed. Though he started well with his training, he was blown off course by a return to Somalia and a reunion with his twin brother. A two week trip became a two month stay with his family, and Mo admits that in the following year his heart was not in the sport.

Mo had left college hoping for a change. At this point it was quite possible that like many other young athletes, he would not make the transition to adult professionalism.

So what changed Mo?

The answer comes with a stay he was offered at a low rent in a house in Teddington. The house was used by Kenyan athletes while they were staying in Europe to take part in various competitions around the continent.

At this time, there had long been a limiting belief among British and many European runners that the Kenyans were in a class of their own. The thinking was that it didn’t matter what the Europeans did, they would always be outclassed by their African rivals.

Mo began to see things differently. By living among the Kenyans and taking part in their training regimes, he discovered that the key to their success was not necessarily a natural or biological advantage, but their extraordinary commitment to their sport.

On his first night staying in the house, Mo was astonished to see them go to bed at 8.30 in the evening, and get up at 6 am to eat home cooked and simple foods, including ugali, a kind of Kenyan maize dumpling rich in carbohydrates. The team would train, then take part in a long warm down. They would sleep in the afternoons to allow their bodies to recuperate, then in the evenings watch videos of runners and races, analysing techniques and discussing strategy. It was a completely professional approach.

Having come from what he considered a high level of training and entering into this new regime, Farah was struck by how much a way of life the Kenyans regarded their running. He began to train with them, stopped going out in the evening and even changed his telephone so he wouldn’t be distracted by friends who wanted to go out.

From being a happy-go-lucky and not entirely focussed young man, he professionalised. The effects of that experience with the Kenyans, of his decision to dedicate his life to his running – and of later visiting Kenyans athletes in their home country, were revealed in his new abilities on the track. Soon, he began to beat East African runners, applying their own training regime to win against them.

It was nothing short of a turning point, and Mo’s limiting beliefs were broken.

After his double gold win at the 2012 Olympics, Mo ran his way to global recognition – and his celebratory dance, dubbed The Mobot further helped him to stand out in the public consciousness.

Since then Mo has gone on to become the most decorated person in British athletics history. In 2013 became the first British athlete to win two gold medals at the same World Championships, his five gold medals at the European Athletics Championships make him the most successful individual athlete in the championship’s history and this year at the Rio Olympics he claimed another two gold medals in the 10,000 and 5000 metres. No wonder runner Brendan Foster has dubbed him “Britain’s greatest ever athlete.”

Part of the lesson that Mo teaches is that in order to be with the best, it is vital to learn from the best. Support from the establishment is a powerful plus, but you have to find exactly how you are going to go forward to beat the world. Watching and learning from the Kenyans gave Mo the extra push he needed, as he modelled their approach to training and then combined it with what was on offer from GB athletics. It is that realisation that transformed Mo into an international athlete of the highest order.